Savor a glimpse of pre-9/11 Afghanistan, a land of human warmth, harsh beauty, passion, rich culture and humor that completely captured my imagination as an adventuring 25 year old in 1970.

Background: In the early 1970’s young people flocked in all sorts of ways from London to Sydney and vice versa. I’d made my way from Australia via hitching, police boats and donkey carts to join up with Tim, a Peace Corps friend, in India. As we traveled, we’d learn from others what lay ahead. Like everyone else, I read Michener’s Caravans and, like everyone else who read Caravans, I determined to go to Afghanistan. (*Note: Sorry, no photos. I didn’t want the distraction of a camera to take me out of the moment. Now I wish I’d carted one.)

16 July, 1970 — Some God-Forsaken Wayside Village in the Punjab

Just too simple for us to get on a bus and simply slide out of India. The Indian system came through again and, of course, our jalopy bus has broken down. I suppose we’re lucky there is a relatively cool breeze amidst all the dust while we await whatever bus happens along. Nothing for it but to expect to stand up or be squashed in the bus for the rest of the way to the Pakistani border. Such a layer of dust collecting on me and my clothes and gear. So uncomfortable being watched by the clustering, staring and sniggering children.

July 17, 1970–Landi Kotal Bazar

The scenic wonders of the storied Khybur Pass and its inhabitants. I’m able to savor it interminably since we have continuous waits between busses and trucks, or whatever. Stopping frequently without fail–time for tea. I get so impatient after it happens for the 15000th time. Despite its exotic history, the landscape is barren and uninspiring. Terraces of dust and rock extend for miles, with occasional mud-packed walls and mud-colored houses hidden behind.We see no women. Only men–wearing gold and/or white pillbox caps, long vests over long bush shirts, baggy pants, rifles in hand, cartridge belts slung over shoulders. Annoyance of being a female in these countries where no facilities are provided for anyone.

At last we trundle onward, stashed into an incredible vehicle—a decrepit truck (?) with men outside hanging off every gripping place and, inside, squeezed into every corner, with packs between the feet of me and everyone. Two huge plastic bags of tomatoes are crammed under the gas pedal and clutch.

Jallalabad–17 July, 1970

Such bleak, rocky, country with horizons obscured in dust. We cross countless wide, stony, dry riverbeds. Mud style is the only architecture. Night is falling as our valiant vehicle lurches into the tree-lined streets of Jallalabad. It’s a festive feeling. Music wafts out of shops and parks. Fruit vendors stand on corners. Savory smells assail us. Gaps in whitewashed walls hint at hidden gardens. There is a feeling of being in the Asian Soviet Union. The features of the people are not dark as in India, maybe it’s more Moghul or Persian. More Greek or Italian.

My burning thirst is quenched only after five Sprites, Fantas and Shezans. We feast on pulau and fruit. It’s too late for a taxi or bus to Kabul so we opt to spend the night sleeping in public bunks on the cool veranda of a hotel with an open-air shower.

18 July, 1970 — Kabul

We catch the 6:30 a.m. bus, having slept well despite car horns and music blaring. Once again we’re crammed into a dust-encrusted, colorfully painted over-full vehicle. It’s me, the one woman, and an armada of men, all in their pillbox caps, and cradling guns. All dipping incessantly into their little tin canisters of-–what? Tobacco? Snuff? Hash? They chew or inhale it and then spit. Spit, spit, spit. Everywhere.

Our bus climbs ever-upward through ever-bleaker country. I’m impressed, however, with the technical skill and efficiency shown in the dams, roads and tunnels we pass—all built by foreign nations. China, the Americans, the Russians, Iranians.

Kabul is a disappointing city upon first entering. It’s like a Siberian border outpost with wide streets and rough buildings, surprising us occasionally with some very modern complexes. Women in burqas in a variety of colors, some are knee-length, revealing mini-skirts, and shapely legs. Their Hollywood sunglasses seem incongruent. Many women are western dressed but not quite with a western look. Men in thick-wound turbans like medieval merchants. Camels and sheep. Taxi fare is the same price as the bus ride up from Pakistan.

We found the famous Khyber Restaurant. Nothing special. It’s meant for regulars, but the tourists flock here in shorts and beards and leave their VW busses lined up outside. Innumerable karakal wool coat and leather shops line the streets. Men everywhere in wool beret-type hats. Stores display Soviet and other goods uncommon to my experience. It’s a pleasant feeling walking amongst these people, easy to walk alone while Tim shops. There’s friendly banter, but not rude. Stalls. Photo stands. Fruit. It’s hard to find soft drinks and they are expensive. I’m eating too much bready stuff. We are congratulating ourselves on not having yet succumbed to the ravages of the food and water. It’s like playing musical chairs from meal to meal. We’re still in the running after each meal, but we wonder if we’ll make it to the next one.

19 July, 1970 – Kabul

It’s like being on a honeymoon here in Kabul. Last night we stayed out exploring and feasting on glorious food. This morning we rise late and go to the Khyber for a breakfast of strawberries and yogurt. We found our way to the Peace Corps woman, Denise’s, and chatted with her and her Afghan girlfriends and readily accepted her invitation to join them tomorrow on their trip to Bamiyan, where the buddhas are carved into the cliffs.

In the afternoon we go to Shari-Nau, the embassy area, pastry–hopping and gun shopping. Kabul is growing on me. I love the features and the exotic attire of the people and the pleasant banter with the shopkeepers. The bargaining is for fun, not pressurizing or personal. It’s almost as if they know it is part of the role they must play, and so they appeal to our senses of fairness and humor to make us go along and give a fellow a chance anyway.

The biggest problem is finding out where the bus to Bamiyan leaves from. At 3 a.m., yes, everyone tells us that. But where?

20 July, 1970 — Bamiyan

We tiptoe from our hotel at 2 a.m. Kabul seems even more like a frontier outpost in the dark of night with its shadows of rough buildings and flickering of gas lamps along the wide streets. Dogs bark furiously as we pass, lurching under our backpacks, over the cobbles and stones of the dirt avenue. Down a dark side street and through an alley and around a corner and inside a mud wall we find the bus—full already with people.

We establish ourselves on the roof and are awed by the amount of luggage already piled on. Then the men start working in earnest and take on an incredible amount of bedrolls, packs and trunks, all the while pushing us aside and wishing us off the roof. But we refuse to yield our places, knowing how easy it is to be superceded by anyone who moves quicker and pushes harder.

Around 3:30 the bus grinds into motion. The air is sharp and cold enough to warrant wriggling into our sleeping bags. Within minutes, there’s the first prayer stop before starting the climb up the mountains, and we can look back at Kabul sprawling pastel and dim in the predawn light.

Chugging across a wide plain we see trees, mud houses and crops in abundance. The dirt road winds along the contours of countless fertile little valleys. It seems the barren gray slopes always converge in the V of a river, and here the people live in simple mud huts tilling the available soil bestowed by the river. Sometimes elaborate ditch systems conduct water to the fields past, and even through, houses and for miles along the slope of a hill so that crops can be irrigated higher above the river land as well.

Not too many stops. One for nan (flat bread) and chai (tea) in an open-air “café”. We sit crossed legged on reed mats or woven carpets with little tea pots and even tinier glasses. When we pile back into the bus, I peer in through the windows and am astonished at how crowded the people are inside. How grateful I am that we’re up on the roof and can breathe and take in the panorama of the Hindu Kush, a study in rocky pediments, stone formations and shifting colors.

Lunch stop. We break nan into tin panikins of tasty soup and sip highly sugared tea. We skip the tough looking meat, but take the risk of savoring some juicy, plump grapes. Away again, swaying in our high perch, absorbing the intense sun rays, talking with the German man with the straw hat and movie camera and the Aussie chap with the blistering nose. Our conversation is overtaken for a spell by three little Afghans, jabbering, singing and spitting. One in particular is a nuisance. Only after a while, do I realize that the strange feeling I’m having whenever we are all forced to lie down to avoid branches of trees is this little guy reaching over and groping my chest.

I change places with Tim and soon a squint-eyed fellow starts cuddling up. But he is harmless, squinting out from under his enormous turban and babbling to nobody, like a child or a moron, to his heart’s content.

Late afternoon we begin passing through spectacular scenery. After climbing the switchbacks of a pass we drive along vast, open, rolling hills with tussocky grasses and a tundra-looking appearance sweeping toward the peaks of high mountain ranges off in the cloudy horizon. Then we start descending narrow gorges and soon, instead of being at the top of the world, we are at the bottom gazing up at magnificent, towering rock faces. All are rugged and eroded, sometimes into weird patterns and shapes.

This chasm eventually widens and follows a swift-flowing, clear river edged by lush, long grasses, but with an absence of houses or people. Above us jut twisted and jagged red rocks, pinnacles, and rows of pyramid peaks and sharp ridges. The late day shadows intensify the patterns of fantastic forms and colors. We pass the 800 year-old “Red City”, abandoned since its destruction by Genghis Khan 500 years ago. Crumbling walls and towers rise out of the hillside on which it was so grandly built, watching down centuries, solitary sentinels of a life unknown to those beyond these mountain barriers.

We see caves gaping in the red stone cliffs. Now the road is lined with more and more trees whose branches we must scramble to dodge until finally we are forced to evacuate our airy bus top and enter the crucible of the bus. My western mind boggles entering the cramped space in which dozens of crammed people were contorted for 14 hours. The loader literally walks over me. We take up positions as fantastic as the rock formations we’ve been passing. At 5:30 we arrive in Bamian and quickly find the guest house. It’s alive with lots of young travelers, but no Denise. Evidently their plane didn’t leave yesterday. Pretty rustic for 60 cents a night. We eat and are into bed by 8:30.

21 July, 1970–Bamiyan

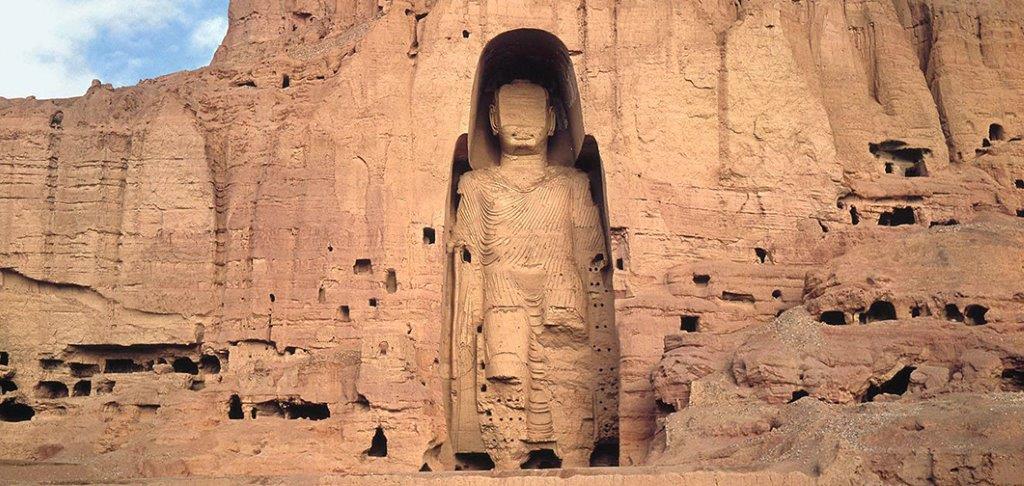

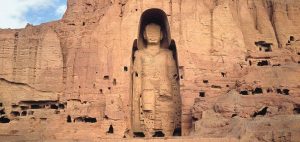

The German boy and I relish scrambling up the red stone hillside where for 1500 years the eyes of lidless caves have looked out over the mud-walled houses and the fertile fields of the Bamiyan Valley. Here, at the western end of the Hindu Kush, (which means Hindu Killer), we can see the rising ranges of the Koh-I-Baba (Grandfather Mountains).

After traipsing up and around numerous passageways, we encounter a wooden door. Hans unwires the lock and we slip through the cool, dim passageway right out to the head of the Buddha. Sitting atop the crown of the 175-foot Buddha, I can imagine Bamiyan’s once-thriving monasteries and bazaars and can conjure the town that became known as “The City of Noise” when, in vengeance for the death of his grandson, Genghis Khan destroyed all its citizens. *

Descending the hill, we join others sitting in the little tea stall under the waving shadows of breeze-blown trees and eat elegantly sliced fingers of juicy melons. They are pale green and delicate, sweet and refreshing unlike any melon any westerner has ever tasted. Tea. Friendly smiles of tea-drinking patrons in long robes and thick-wound turbans. Peace and sunshine and cheerful shade. A moment out of time to savor and remember.

The German boy and I cannot get enough of this strange, still, Buddha-hillside and are drawn back up it at sunset to sit toboggan-style in the lee of a ditch. We share one joint, and watch the incredible bands of shadows playing across the changing faces of the hills and mountains.

* Note, 2001: Who would have imagined that 31 years later the Buddhas themselves would be destroyed by the Taliban, thus eliminating in one swoop the 1500 year link with the past and the livelihood of Bamiyan’s remaining citizens.

22 July, 1970–Bamiyan and Band-I-Amir Lakes

By jeep to Band-I-Amir. Our little group–the Swiss couple and Hans, Ira from Illinois, Tim and me, swathed in coverings and clothes in the Russian Volga jeep, joking and chatting in the early morning chill. We bounce along the bumpy track, passing beside the beautiful rocky slopes of the Koh-I-baba mountains. After a couple of hours, we stop in the nothingness of this vast wind-swept space for chai and nan and curdled butter.

We continue on, through landscape looking as if it’s been swept clean by a mighty broom. It gives way to rolling hills with tufts of tough, weedy grasses, good only for fire and tinder. Patchy tents of the nomads’ are frequently pitched where the hills yield a grassy crease, their donkeys, goats and lanky camels foraging about busily devouring some mysterious feed. It’s always exciting to see a camel, and then many more, munching their way across a hillside. Eventually we come to know that this heralds the proximity of a camping caravan. We even connect with one family, joining them in their tent for chai and nan, and Hans gives some aspirin to the sick mother.

Cresting a hill, we’re suddenly hit like a blow by our first view of the Band-I-Amir lakes. Here, amidst the dung-dry vista of rocky plains, is the most vibrant, intense gem of water blazing royal blue. Beyond, high above, salmon pink palisades and craggy faces of variegated cliffs form an almost unreal and eerie setting for the blue expanse.

On closer view, we can see how crystal clear the water is. Ledges of underwater rock gleam perfectly defined in luminescent turquoise. A natural dam overflows with mighty showers. Like a hot springs, the minerals have colored and veined rock and earth and, below, the water flows in swift, shallow rivulets, spreading fans in a broad descent to the next terrace, and the next…. On the shore stand horses, huts, donkeys, VW busses. We picnic on omelets and tea, gasp in a swift swim, walk and talk. Always, the people one is with color the environment, no matter how spectacular, unless one can escape to solitude with nature.

After much haggling, our driver agrees to take the Dutch couple on the jeep with us. Back at our Bamiyan guest house we savor hot-dippers of bath water and a delicious meal of Kabuli pilau sitting on the Persian carpet. The room is crowded with kneeling, squatting, talking foreigners and a few smiling-on Afghans. Tonight we sleep with eight in our bedroom.

Puli Kumri — 23 July, 1970

By 7 a.m. we depart Bamiyan, standing braced in the bed of an ancient truck. Like babies in a crib, we grip the bars and peer out at the harsh infinitely impressive landscape. Our truck lurches along the centuries-old sandy riverbed road, eventually turning off our path of the first day to zigzag around the bends of a violently deep gorge. Steep faces of twisted, churning, craggy rocks vibrate in golds to russets to blacks, grays, pinks and browns. At strategic points, crumbling watchtowers appear overlooking the approaches from precarious rocky heights. Once, we see a fortress with a still-visible wall sprawling up and down and over the whole hillside.

Around noon the truck halts at a second tea stall where trillions of turbaned men sit drinking tea. Strange. Such a bustling spot in the middle of empty hillsides. We never expected practically the whole tea stall to get up and converge on our truck. Fortunately, the driver made sure that I was already ensconced in the top crib overhanging the cab of the truck from which I could look down relatively unaffected upon the swarming field of squash-shaped turbans. Even so, where we had been three, we became ten, with hobnailed shoes digging into thighs, knees into ribs, and rails of the cage bumping soft skin as we roll onward. I am lucky. The fellows fare far worse, squashed as they are in the bottom of the truck bed amidst several dozen sizable, squatting, jabbering, spitting, Afghans.

From my swaying perch I view walls of vermilion rock, deserts of convoluting cordovans; play of shadows on craggy cliffs, russet of rocky, sandy ranges; river valleys hidden eventually by the very numbers of the folding ridges. A lunch stop for delicious soup and eternal nan. The kind driver hustles the four of us back to the truck and packs us in the desirable front basket over the cab. Even so, a couple of quickies see what he is up to and race over to push themselves in too.

Did we really sit with legs bent double for five hours and no time or place to stretch? Drops of rain spatter and under the sleeping bag we wriggle toes, fidget in turns, twist an ankle or a thigh and pass the time giggling at ridiculous commentaries on our circumstances. Muscles, bladders and bowels are strained to precarious points of endurance when, at last, we collapse out of our little basket here in Puli Kumri and make our way, dazedly, via darling, colorful horse cart to the Klub Hotel–with showers! Two hot ones and two cold ones. Worn out, we head back to town for a meal and a quick look, buy a melon, and come home to fall into our four beds.

25 July, 1970–Bazaar at Puli Kumri

Today, blissful immobility, not to get up to a bus, jeep or truck. Not to sit getting to know the real Afghanis—elbow to knee by ankle. To sleep until the need of it has been satisfied, to stay abed until the urge moves us to arise. Delightful to sit over breakfast of fragrant melon, tea and iodine-soaked raisins and to talk or read until noon. Our little group of four gets on well. I am glad of the company of Hans and Ira. The travelers we’ve met have so contributed to making this trip fun and interesting.

We walk to the bazaar, past streaming swaths of cream, indigo and saffron turban cloths drying on the ground alongside the road, past water splashing merrily down culverts irrigating terraces of grape vines. We walk buoyed on air redolent with the fragrance of ripening grapes.

The bazaar vibrates with noise and color. Sumptuous wares greet us at every glance: fruits, especially grapes, beautifully displayed; patient donkeys standing under twin hemp baskets piled high with deepest, purplest eggplants and huge gleaming tomatoes; richly embroidered patterns of the nomad women’s dresses; hanging carcasses of the fat-tailed sheep; multicolored saddles, woven blankets and belts; jingling jewelry and brilliant kerchiefs of the women–when they are not moving like nuns under the draping burkas; the men’s pillbox caps woven in intricate rainbows of gold and other colored threads, their ballooning pantaloons protruding beneath the calve-length tunics; clattering of the horse-drawn buggies jiggling green and red tassels trotting in the heady air along streets shaded by ancient, majestic pistachio and pine trees.

We inhale aromas of roasting meat and oil and the pungent perfumes of herbs and spices. Lunch is another feast of visions and smells. We climb on to the raised floors of a café where turbaned men and foreigners sit on brightly woven rugs receiving great platters of pilau and omelets dripping with oil, raisins, pistachios, and tasty mutton. Our senses satiated beyond sanctification, we head back to the hotel to rest, read and write.

26 July, 1970–Puli Kumri–In the Home of Aziz

An invitation last night to the home of an Afghan student became a happy and memorable experience. Tim was caught up in the search for his lost or stolen passport and travelers checks so was not there. Hans and Ira and I found ourselves exotically entertained reclining on the mauve mattresses and white silk cushions in the house of Aziz. Four brothers were the main entertainers, although we met two girls of the 17 children and the married daughter with her husband and children.

They could have been an American family…the boys with their butch haircuts and the girls with hair in curlers under scarves. We played “Karambal” and then Tosha Kor (“Thank you”), a card game that was lots of fun, especially due to our bilingual method of playing: Deal out the deck and then X asks anyone for a card, for example a 7, but only if he himself holds one or more in his hand. The “requestee” must yield the card asked for if he has it and the Requester must say, “Thank you.” If he forgets to do so, the card goes back to the owner and the owner can now request “one 7” and it is his turn to ask players for cards. The game gets exciting and funny because so often people who under ordinary circumstances automatically say “thank you” for the littlist thing, forget to in the heat of the game. Even more funny were the ludicrous and brazen attempts at cheating that we all employed.

The game was interrupted for dinner, placed on the floor in front of us by the girls. Delicious, not because of elaborate preparation, but because of the food itself. Eggs, salad of tomatoes and onions with mint, soup, honeydew and water melons in heaps, juicy bunches of purple grapes, curd, chokka (“brother of yogurt”) and always more, more to be dipped into communally, each with our own piece of nan. The Afghan wine was amazingly potent. 40% proof, I think, homemade and impossible for me to consume greatly or quickly

After dinner, we returned to our card game and finished it once we’d all got groups of fours by asking one another for the fours and using cheating methods to help us remember what cards each other had. Rather nice that Hans won. Out came the hash. Amazing stuff. Three puffs and I was high as a kite. So full of laughter. Couldn’t do a thing without laughing, and Ira across the way, cracking up too. The whole family was enjoying the exhibition tremendously, each of them puffing contentedly on a joint as it came around to him. How many homes does one get into where the hospitality extends to having the old hash box brought out? Like offering a liquor or after dinner mints.

Singing and all of us “dancing.” Laughter. Leave around 1:30, stoned. Aziz and his brothers walk us home and, a pity, it sort of disintegrated the lovely evening for me for they started patting me and squeezing me. One fellow passed me some hash as a gift and gave me a great squeeze on the breast. I got paranoid and started singing “Whenever I Feel Afraid,” hoping that one of my boys would walk on the other side of me. Finally Hans and Ira got the idea, but didn’t fully comprehend. Touching western women must be practically a national action. Still, I just couldn’t hate the Afghan boys, they’d all been so fun and sweet all evening. I can’t understand, though, how they could become so entirely different once out in the dark street and after such an evening of what I had taken to be mutual respect and humorous rapport.

26 July, 1970–To Mazar-I-Sharif

After a lazy morning, we depart Puli Kumri by bus. A crowd of—I swear–400 men in the tea house listening to a harmonium now all converge on the bus. These Afghans have a talent for molding themselves into tiny corners and into the folds of each other’s bodies and always seem to fit ten comfortably into a space where three westerners would expire. It must simply be the course of things. None of them has ever sat on a bus or truck that was not cramped and stuffy so they simply accept the whole journey of discomfort and smile and chat or doze all wedged in like pickles in a canning jar. But for us, who have been raised on the luxury of space, a bus or truck journey becomes a prolonged plunge into agony. We watch the clock and measure the hours to the half-way point, study the mile posts, daydream or read and try to make it come to an end by removing ourselves as much as possible.

The country is magnificent in its harshness as we pass through weathered rocky ranges that have seen eons of snow and sun. Irrigated areas along a river or trickle of water look especially beautiful, refreshing, soothing and abundant surrounded by the arid land and surveyed by blazing cliffs of twisted rock. Sundown, orange glow, and prayers. I admire how these people interweave their devotion into their daily lives, instead of trotting it out once a week or year, as is so common for westerners. Camels and yurts. The wide, empty desert — rich blue-black. Stars few, but brilliant. Orange and green lights inside the bus. Periodically mud walls loom along the roadsides and we see shadows of men on donkeys, carts, and horses. The incredible isolation and loneliness of myself, of man, sweeps over me.

27 July, 1970–Mazar-I-Sharif

A galloping ghody (horse cart), bells jangling, hooves clattering, whizzed us here to the Ariya Hotel in the dark. We dive under showers and then blissfully collapse into clean beds. It’s so hot, we eat and sleep on mattresses moved outside. Many French tourists. And just across the riverbed to the north is Tajikistan—Russia!

Today we are driven the 7 kms out to Balkh, a storied place connected with Alexander the Great. Known as Bactria, “Mother of Cities,” it flourished as Alexander’s Asian capital. We silently take in: crumbling sentries of eroded brick and mud stand mute; the Bala Hisar, a ruin overseeing these ancient heights, with eroded clay sides still thick and steep and cut by an ancient arch; the mosque–patches of vivid turquoise tiles still clinging in their intricate patterns to its sides, its dome still gleaming like a salvaged shell from an ancient ocean, in the midst of all the dust and decay of the present. Snowy pigeons coo, at home in the many choice spots provided by crumbling bricks, becoming brilliant contrasts to the patterns of blue. We clamber up the almost non-existent steps of a tower staircase and emerge standing in the rubble of ages accumulating on this little circular shelf. A camel train undulates below, jangling colorful, well-balanced loads, led by a donkey.

Intense heat, so dry, dusty. We truck back to town (cost is 5 Afghanies (about 25 cents) Saved ourselves 580 Afghanies by not choosing the little man with his package tour. Home to cold melon and water and to rest, read, shower and enjoy the occasional breeze, warm and dry as it is.

At sundown we visit Mazar-I-Sharif’s famous turquoise mosque. It’s prayer time. Rows upon rows of the faithful are bowing down and kneeling barefoot in the court yard facing the west. It’s questionable whether Ali, Mohammed’s son-in-law, in reality is entombed there, but that doubt doesn’t detract from the delightful effect of color and intricate design. All this glorious beauty and it’s only mud underneath. I resent a religion, a group of people, however, that discriminates against me as a woman so that I am not allowed to go in with the guys to see the inside.

28 July, 1970–Puli Kumri

Here we are, back again, after several centuries of discomfort. While waiting in Mazar-I-Sharif to meet the bus at noon, we walked the street, enjoying the carpet and camel bag shops and drinking chai with the shop men of last night. We exchange smiles and glasses of tea–thick with a two inch residue of sugar–as we sit cross legged on the rich red and black plush of carpets, camel bags and tassels.

Melon—“backsheesh”–a gift from the carpet man, and later so nice to eat as we wait for our 8:30 a.m. bus to get going. Wait and wait. Climb aboard. Wait. Lurch to life. Drive around the road divider. Stop again and wait. Load up again. Drive around the divider again. Wait again. Drive again. This time up to the mosque—then back. Wait. Load. 1:30, away.

Within the first 100 meters, it’s plain this vehicle has water problems and an extremely overheating engine. People are crammed atop one another, and we’re lucky to have elbowed ourselves into the front seat. Even so, it’s HOT. Swiftly, I’m overcome by chills and stomach pains and feeling stifled by the fumes and heat of the engine. I trade places with Tim and am better by the window. Damn.

Thinking never so much of having a journey quickly end, and of course we WOULD be on a Russian crate on its last legs. It is virtually nursed by the driver and his bacha (helper), along with a 40 gallon drum of water atop the roof connected by rubber hose to the engine. The drum is hand-filled and refilled from any muddy ditch. I take advantage of a radiator stop to make an awkward nature call. Miles of empty desert and not so much as a blade of grass, let alone shrubs or trees. No mud walls. Nothing to do but squat beside the bus in wide-eyed view of every passenger.

The “four” hour trip that had been five hours before was nearly seven hours today. Wonderful to at last get a ghody and make for the hotel, there to sit on the cool grass of the garden drinking tea until we head to our favorite restaurant for Kabuli and kofta, then back for blissful hot shower, back scrubs and laundry.

29 July, 1970–Kabul, Helal Hotel

There were numerous opportunities for busses, trucks, taxis, leaving Puli Kumri. Eventually we travel via taxi with three Americans. The cab chugs upward through the famous Salang Pass on the Russian-built road and through the tunnel which at 10,000 feet, is so impressive for its artistry. This concrete structure could have been so utilitarian. Yet it is constructed in concrete “V’s,” and cleverly uses light and shadows to enhance the intricate designs. In these high mountains we see no life, only tumbling, clear, cold water, rock, and snow in the high valley folds. At last, Kabul, into a stuffy, hot room. We made it. Even in the comfort and ease of the taxi, it is a long, tiring trip.

2 August, 1970–Kabul – Sina Hotel

Days pass with a convergence of details. Tim first attends to the recovery of his passport and takes the steps towards getting a temporary one. Then the ordering of the karakul [a fine, soft curly wool] coats, a truly time-consuming project. We spend an entire morning trying on coats and deciding on the designs and then, with patience and apparent unconcern, talk the shopkeeper down to a less exorbitant price. Even so, they will not be cheap, but I am looking forward to their completion. My coat and boots will be a beautifully crafted and elegant outfit that will last the rest of my life. (Note, 2002: Ha! My gorgeous Anna Karanina boots were devoured by moths in Portland, Oregon. After that, I didn’t want the coat any more,)

The Helal Hotel proved to be less than the fine place we’d been led to believe, so we made a deal with the manager of the hotel across the street. He agreed to let us stay in the top “pent house” for 40 Afghanis a night. We trudge up the five flights of stairs, clean ones at least, and enter a six bed dorm, completely englassed on four sides. It’s a fabulous height to overlook the city and gaze up to the surrounding camel-colored mountains with their mud brick walls, the early defenses of Kabul.

3 August, 1970–Kabul – Paghman:

Paghman, the central park of Kabul, sits 16 km from the city. Levels of affluence are seen in steps here. If you have a car, you drive the dusty distance up to Dara Park, sprinkled with bright beds of flowers and traversed by little ditches of clear-running, cool water. People sit in the shade on the green lawn and eat melons and cherries. There are families with women in colorful chardres, men in suits and karakel hats, children in knee sox and short dresses, young men trying to appear very much the men of the world in open throated shirts and jackets slung over thin shoulders. Some of the families look strangely western in their shirts and ties, best dresses and bell bottoms, and wearing big, round sun glasses.

A new group arrives—several men strolling in suits with transistors or cameras under their arms while one serving man bends under an enormous load of quilts, carpets and paraphernalia that would provide bedding for at least 20 people. Lower down, the not-so-affluent remain with their card games and food stall single dishes or drinking glasses, and their simply-made balloon and dart games. People stroll here and there along the shady, meandering dirt paths. A friendly family shares their cherries–a policeman who had studied in Germany and his good looking wife and many mothers and aunts-in-law in addition to his own family.

4 August, 1970–Kabul – Faiz Hotel

Reinvigorated on and off by the shock of cold plunges in the swimming pool at the five star Bag-I-Bala “Intercontinental” Hotel. All day we lie in the clear, warm sun on deck chairs, reading or absorbed in our own thoughts and gazing at the incongruous vista of mud houses and nomad tents dotting the baking barren hills around us. From the burning hillside behind us, many eyes of square-holed windows stare at our luxury and ease. There are no trees, just slopes of dung-dry shale and rock, earth colored from the base to the peaks.

Four kind men, the Ariana airline steward, a doctor, the student and the army officer, with their little fatherless girl, all shared their lunch and their whisky with us. Afterward, they showed us this hotel and we decided it was preferable to our five flights of stairs and our glass cage, so tomorrow we’ll move. Again. They also tell me about a job opportunity with the Czech airlines. No doubt opportunities will come up again and again. All I have to do is say “Yes.”

I mention jobs to everyone we meet. After reading in Michner’s Caravans about the Afghan national sport, buskashi, I’m determined to see the polo-like game where teams gallop at breakneck speed on the field tossing a dead goat back and forth. Typically players are maimed or killed. All I need to do is find a way to hang around for another three weeks because buskashi will be featured at Jesshin, the Independence Day Celebrations at the end of August.

5 August, 1970–Kabul – Hotel Baqir

I’m sick to the gills, belching out my posterior all night and this morning. I should never have eaten bolani* last night, but the famous dish was so tempting and such a taste treat. We found the bolani stall hidden behind the rows of mud and clapboard shacks, where a huge skillet sizzled over a gas fire and a little man rotated potato and leek turnovers. Behind him, his assistant patted out balls of flour and water dough and, never breaking his rhythm or precision, rolled them into impossibly thin pancake shapes. Dust, roll and toss. And now, agony–my stomach bumping and grinding tumultuously.

Today I met Mr Marikyar of the Czech airlines, and he turned out to be the manager of the Marco Polo Restaurant. He offers me the “coordinating manager” position at the Marco Polo. He needs someone who speaks several languages to liaise between the Afghan waiters and the foreign patrons. Not that my language skills are so great, but I think I can improvise and certainly, I speak a lot more than someone who knows none.

In some ways night work suits me and in others, it doesn’t. I don’t know how good a boss Mr Marikyar is. I think he runs a pretty knuckle-down, strictly impersonal, no joking around kind of show. Still, it’s such a perfect situation for meeting all types of international people, and to practice languages. And it means I can be here for Jesshin. Yes, I must accept. How many foreigners have such opportunities? If it’s really rotten I’ll simply leave.

10 August, 1970–On My Own in Kabul – Green Hotel

Yesterday Tim left for India, and then it was 4:30 pm, time for me to step out into the dust-rumpled dirt and rocky street and pick my way over the piles of cobbles to my night work. To my work that is not really work and that is not really exciting, and endure it for six hours, all the while knowing that there is no longer any Tim to meet me afterwards.

But it wasn’t lonely, for the Canadian boy came in at 11:00 and after a long talk and tea, he offered to walk me home. It was an excellent chance to bring my gear over to this new hotel, and he was willing to help. So I checked out of–what? my 4th hotel?–at 1 a.m. The walk back through the dark, deserted streets was so comfortable with another person. Once here, I was too tired to care that there were no empty beds in the dorm. I just plopped my sleeping bag on the floor, along with multiple other sleepers.

Today was the real feeling of emptiness when this new friend, as well as Tim, was gone. But interesting adventures supplanted, beginning with a prolonged series of trips to the toilet that was agonizing because the only two toilets were being sought out and hibernated in by the majority of the 50-odd residents in the place.

14 August, 1970–Kabul

At work, bored at first, but then we were busy. I enjoyed seeing the patterns of farsi words developing as the waiters have their nightly fun of teaching me phrases that I try to repeat most unphilologically. We seem to focus on vital food-related phrases, like, “I like ice cream,” Man hosh taram sheerya, “I want ice cream,” Man mayhaham sheerya, and, “I am hungry,” Man jafa hastam. My other frequently used phrases are about leaving work. “What time is it?” Chand bajah ast? and, “I go home,” man honam mayrawam.

16 August 16, 1970–Kabul

Tonight at work, taking looking after the Canadian Ambassador and his nice, common-looking, pleasant family. Even he had to be refused his order, along with numerous other people. I had to go through the old, “I’m sorry, but X is finished, Y is finished, etc,” routine. I was also teased off because the waiters wouldn’t allow in a man dressed in Afghan clothes.

22 August, 1970–Jesshin—Independence Day Celebrations

Strange, the developments of the day. I’m not really sure what led me out to the American embassy except to inquire about rides to India and only on second thought to check my Afghan visa. The man there informed me that my visa had already expired. (How could I know? it’s all in Farsi.) I was beating it for the police station to do my duty by the officials and their system when I was summoned back to the guard gate and to the telephone and requested to go to room 123 and maybe the man could help me.

I’d been “waiting for something to happen,” and from that moment it certainly did. He fed me donuts and coffee and started the wheels turning with phone calls and inquiries which eventually led to my being escorted in a staff car over to the police station and having his friend fix it up for me, without a fine. Then I was taken to lunch and dropped at the Ariana Airlines office with an invitation to dinner.

My last night at the Marco Polo yielded a rather muddled leave-taking. Fortunately the French girl and her husband came along and were immediately put to work, Marikyar at last paid me my 2000 Afghanis, and I could go. I’m not sorry, because this frees me up to see the Jesshin events.

23 August, 1970–Kabul

This morning I eagerly walked down to the festival area alone, and retreated quickly once I was swallowed into the eddying throngs of Afghans. I got extremely uptight and hard-bitten as I had to fling out to keep back the men in the crowd who reached out obscenely to grab me. I wonder if they treat their own women this way. Local foreigners explain that the Afghan men see western movies and assume that western women are all panting for sexual encounters. Yet, I can’t buy that because every manager or owner in the hotels I’ve stayed in—and evacuated because of their advances–has been wealthy and educated in England or the US. Surely they know otherwise.

I was very disappointed and my stomach was bugging me, so I simply had a breakfast of tea outside the Kyyber Restaurant and watched the milling throngs. The couple with whom I’d made friends in the Marco Polo one night walked past, so I caught up to them and am so glad I did. It’s comfortable and fun strolling around with them and sharing the parade with countless military tanks, trucks and jeeps thundering past literally tearing up the road with their caterpillar tracks.

Afterwards we visited with their friend Gary under the trees outside their tents, sharing conversation, information and questions until 1 pm when we hurried back to the festival area to get in on more of the day’s events. We were just in time to catch a lift on the bus with the Russian soccer team down to the stadium. Where else would the organization be so loose that five of us could just pick up a ride with the team and then be escorted through the players’ entrance to sit in the Russian section?

I was inwardly thrilled to find myself for the first time surrounded by a community of Russians, even if they were comprised solely of over-age diplomats and visiting footy players. They were Russians and I my long fascination with Russians and learning their language was rewarded as I watched them, listening to their comments, noting their clothes, haircuts, sideburns…. Very strange, the attitude that this political power conflict has nurtured in me and others, both Russian and American. Mostly, I’m curious, wanting to see how they go about ordinary things. We enjoy sharing with them the pleasure of the good footy plays, successful goals and humorous incidents of the game. The other three teams were from Afghanistan’s other “friendly” neighbors—Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan.

The team bus ferried us back to the Arian Hotel with the Russians. We went inside for tea, and then the evening suddenly developed. The Russians came downstairs and soon it was not tea, but vodka on offer. Vodka straight. Something I never even dreamed of in my wildest degeneracy. But surprisingly it was smooth as silk and went down easily with a za nash zdorove! (to your health) and za meernaya sosushestvoveniya! (to world peace!) Soon, along came the bread and radishes, tomatoes and cucumbers, followed by pilau and meat, and more vodka.

I surprised myself at the amount of Russian I began to converse in, and as I got tipsier it improved and even flowed. Grammar-schrammer. Who cares? Not me. Not the Russians. Our Russian hosts kept us entertained and astounded by their tricks with coins, glasses and handkerchiefs, and we were continuously laughing at their robust conversation and joking.

Afterwards, at the ‘showgrounds’, I was unprepared for the amazing array of lights and pavilions blazing in the night. But, ho, what a hassle to walk with the throngs, to have to stride with each fist curled and ready to strike out. My reactions are quicker now and I can better anticipate the hands reaching out. It’s good to walk with the other couples.

25 August, 1970–Kabul

Home again to my hide-away laundry room under the stairs, irritated tonight by a neon light fluttering dim and bright, dim and bright. I’ve had two full days of people and Afghan culture. It’s been fun and relaxed sharing it with Trudy, Ron and Gary. Last night, the hotel manager treated me to a fish dinner, a nice man, not self-seeking. Tonight, Mohamed Ebriham, the uni student, was here early to take me to Afghan dancing.

Off we go to the Kabul Theater, an earthern floored hall with clay walls and the smell of feces wafting in on the remote, rare air currents. The “dancers” consist of five or six teenage prostitutes performing singing and dancing numbers, first together and then one at a time. They wear native dress, but garishly colored and assembled. All sport bangs, bright lips, frizzy hair. Some are accomplished at suggestive dancing. One girl is stiff like a stick and should have been a librarian. There are only males in the audience. Men and boys sit enthralled with this pitiful performance. Everyone claps or not as the urge move him, at any time.

Mohamed Ebrahim spoils me with taxis and paying my way, generously takes me to the Kyber and buys not only dinner but a bottle of wine as well. While we were there, the French girl and boy came rushing in pursued by the police and were bodily carried out screaming and kicking while crowds of bystanders stood staring.

7:30, at this morning’s festivities, we all took in dancing from Afghanistan’s guest countries, followed by wrestling. In the afternoon I went down to see the tent pegging and was amazed at how easy it is to find a good viewing place, almost right in front of the ring and peg. It’s a feast of horses and horsemen, oozing with exotic, colorful equipment and apparel. Turbans and flowing trousers and vests. Crowds. Soldiers. Such fine horses, a real spectacle. There are three teams, the army, the police and the native horsemen. It’s thrilling and I vibrate with the feeling of it, loving the horses galloping full-speed with the man and his pitchfork lance.

Our little group concludes the day out at Bagi for a luxurious meal. We are four people thrown together by chance to savor the elegance of our circumstances, to delight in our means and in conversation, and then to finish our wine, looking over the balcony and patches of lights fanning out from Kabul to the array of fireworks bursting in many-colored, multi-patterned splendor over the city with its already-blazing Jesshin grounds.

27 August, 1970–Ghazni

Yesterday morning I was awakened to Gary pounding on my laundry room door. Would I like to accompany him to Ghazni? Yes! I was so pleased to be asked and excited that I actually would get to go there. First, though, I met Mohamed Ebrahim in Sher-I-Nau with apologies that I was copping out. Still, he was sweet and understanding and took Gary and me in the shop of his friend where I bought rifle for 1,000 Afghanies. It costs twice what my original hopes had been, but after looking at lots of guns, I believe this one is worth it. Nothing in all my travels makes such a perfect a gift for my father. He’ll appreciate this antique muzzle loader with its elaborate and beautiful mother of pearl design. Mohamed Ebrahim kindly bought me the powder gourd to go with it. I know that he and his student friends have genuinely enjoyed sharing their culture and their city with me and practicing their English, but I must somehow repay him for all he’s done. *

(* Days and months later, toting my sheet-swathed rifle crossing various border posts, the only customs that did not insist on me unwrapping it to be shown was—San Francisco!)

Gary and I got underway about ten o’clock. The barren hills with their fanning alluvial planes were much more attractive, much less menacing, speeding quickly and comfortably in a spacious VW bus along smooth roadway. Once in Ghazni, famous for its copperware, we enjoyed walking in and out of the fly-ridden shops and viewing the gleaming displays of copper water basins and pitchers. We didn’t buy them though because the prices were so extravagant. Now, back in Kabul, it seems we should have, for the selection here is so much reduced.

We finish the day at the “Soviet Entertainment” in the open air theater. They’ve done well, the Soviets, picking a program of acrobatic acts, dancers and singers, just the level for the audience that watched in turbans and chardrs. Back at the Kyber we find ourselves at a beer-laden table with our friends the Russians, who noisily kept us busy talking and eating quantities of French fries, meat and bread, and drinking bottle upon bottle of beer.

29 August, 1970–Kabul

My time in Kabul is running out. I make a quick trip to the bazaar today, samovar hunting. Samovars are ubiquitous throughout Afghanistan and other Asian countries as well. These beautiful brass vessels with their interior chamber to store coals for heating water have also been mentioned in every Russian novel I’ve read. In my travels I’ve seen samovars in every size. Some tea stalls and restaurants have samovars as big as petrol pumps, able to hold gallons of hot water. Mine is about 20 inches tall, able to just fit inside my backpack. It has some intricate designs and, in Russian lettering; “Manufactured in Tule.”

30 August, 1970–Last night in Kabul

It’s good luck that I will have a ride with the Belgian boys late tonight, even though it means missing buskashi. Such an opportunity to cross the Kyber, Pakistan, and the Punjab right to Amritsar in a comfortable sedan with good people is just too tempting to pass up.

31 August, 1970–Departure

Give me car traveling over busses! Especially in the slathering heat. The option to stop at will, to dip in a passing river, is a lavish luxury. It’s rather ironic how it all worked out. The group of us were up all night finding each other and working out car deals. In the end Gary sold his van to my new travelling companions, and it was agreed that he accompany us as far as Peshawar. There was something about international laws disallowing selling his German-bought van in Afghanistan or Pakistan. So the plan is to for him to make over the van ownership today in the no-man’s area between countries.

I certainly can’t point tardiness fingers at the Afghans. Our 3 a.m. departure is postponed to 5 a.m., to 7 a.m. and then 8 a.m. After an incredible amount of buggarizing around, our little convoy finally departed Kabul. For a last time I take in the rimming, dung dry hills, the rough buildings, the tree-shaded cobbled avenues, the colorful bustle of turbaned men and swishing women. And then we head into the long, zigzaging downward road to the Pakistani border.

This sharing of my 1970 Afghan adventures is twice inspired:

(1st) For my darling “adopted” Hazara refugee family I’m born in California. They’re born in Afghanistan. In 2002 we meet on my doorstep in Australia. Since then we’ve supported each other, shared challenges, joy, love, laughter, Christmas, and delicious food (Zhara’s).

(2nd) For Deborah Rodriguez, who’s books–The Kabul Beauty School and The Little Coffee Shop of Kabul—depicting her feisty, caring, life-changing involvement in post-9/11 Afghanistan captivated and inspired me. For you, Deborah, who shares my passion for Afghanistan and who wrote to me, “You are a very lucky woman to have seen it in that unique window of time.” Yes.

******

Download Article as PDF

© Barbara Brewster 2017